October 25, 2009

My primary approach to the filmmaking process is to think of it as creating pieces of information that, when cut together, create a psychological effect. Therefore, the psychological effect that I want to create must be determined beforehand or I will not know whether I’m getting the necessary pieces. This, for me, is the hard work of prep.

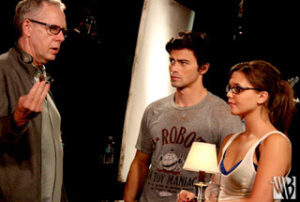

I am always asking myself—what are the psychological components of the scene? And then–what are the visual opportunities that might make the audience understand that? What pieces might the editor need in order to make us understand the scene?

The use of negative space in this shot from ROCKVILLE, CA was intended to make one feel the character’s loneliness.

Truffaut says, “The art of film-making is an especially difficult one to master, inasmuch as it calls for multiple and often contradictory talents. The reason why so many brilliant or very talented men have failed in their attempts at directing is that only a mind in which the analytic and synthetic are simultaneously at work can make its way out of the maze of snares inherent in the fragmentation of the shooting, the cutting, and the montage of a film. To a director, the greatest danger of all is that in the course of making his film he may lose control of it…. Each cut of a picture, lasting from three to ten seconds, is information that is given to the viewer. This information is all too often obscure or downright incomprehensible, either because the director’s intentions were vague to begin with or he lacked the competence to convey them clearly.”

There are many who might shoot a scene in a thorough and exhaustive manner, master, medium-overs, close shots, inserts—a vast amount of material that then allows the director or someone else to create the effect of the scene after the fact, in post-production.

But, without some degree of consideration and contemplation, this can still ultimately end with a vague product. It is essential to have a point of view that will determine the way in which the editor should put the scene together and the way in which a scene will be perceived.

I certainly cover myself when shooting–allowing for options, surprises, revisions–but I approach a scene with a definite perspective about what I’m seeking to accomplish. I expect the department heads around me—the director of photography, the production designer, the costume designer, the editor–to do the same, to ask themselves, what are we trying to achieve here? I will frequently ask one of my collaborators—in what way does this make us feel more or less about what is happening in the story?

I’m frequently asked–as a visiting director on a television series, do you really have any impact on the style of an episode? My answer is absolutely, yes. The camera placement, in any given scene, will determine how that scene is perceived. A well-placed wide shot, a two-shot, an insert, a subjective point-of-view shot, an objective shot—each of these provide a different feeling. It is the director’s job to know what pieces he needs to provide to the editor, in order to achieve the maximum effect. It is the editor’s job to assemble these shots in such a manner as to track a psychological line.

I like Hitchcock’s quote: “The main objective is to arouse the audience’s emotion, and that emotion arises from the way in which the story unfolds, from the way in which sequences are juxtaposed. At times, I have the feeling that I’m an orchestra conductor, a trumpet sound corresponding to a close shot and a distant shot suggesting an entire orchestra performing a muted accompaniment.”

I was inspired by Hitchcock’s SABOTEUR for these shots in CHUCK: “Chuck vs the First Kill”.

The rhythm of any particular scene can be very much like music, and often as each scene comes together, the editing process becomes a musical process—a natural rise and fall, a repeating of patterns. One is often seeking, in a scene, the same type of emotional resonance that is expressed by a beautiful song. (It’s a hard process to articulate but, as anyone who has edited can attest, one knows it when one feels it.)

Essentially, a director determines the visual components while on the set—the decision to include wide shots or close shots, the decision to track or remain stationary. But, while I walk on the set with a strong sense of the elements I need, I almost never try to determine the pace of a scene until I’m in the editing room. It is then that I determine where the pace should pick up or slow down, where the pregnant pauses should land, where the subtext should come shining through (unless you’re doing a long, unbroken tracking shot, in which the pacing must be precise). My actors are frequently asking me, “Shouldn’t I speed it up?” And my answer to that is, “Only if you arefeeling what you’re saying. Take the time to let me see the decision-making happen behind your eyes. Don’t just say the words; decide what you’re going to say next.”

The Russian filmmaker Vsevolod Pudovkin said the following: “The film director (as opposed to the theater director)…has as his material the finished, recorded celluloid. This material, from which his final work is composed, consists not of living men or real landscapes, not of real, actual stage-sets, but only of their images, recorded separately such that they can be shortened, altered, and assembled according to the director’s will. The elements of reality are fixed on these pieces: by combining them in his selected sequence, shortening or lengthening them to his desire, the director builds up his own ‘filmic’ time and ‘filmic’ space. He does not adapt reality, but uses it for creation of a new reality, and the most characteristic and important aspect of this process is that, in it, laws of space and time– invariable and inescapable in work with the actual–become tractable and obedient. The film assembles from them a new reality proper only to itself.”

This new reality can best be described as a psychological state made concrete.

Leave a Comment