June 5, 2015

In December of 2013, Davyd Whaley and I drove up to Big Sur on our way to San Francisco. It’s a sparsely populated region of the central coast of California, where the Santa Lucia Mountains rise abruptly from the Pacific Ocean. We left early in the morning and made it to Nepenthe by lunch, where we sat and watched the birds as we ate.

Afterwards we drove down to Pfeiffer Beach and spent a couple of hours, just walking along the water. We didn’t even talk that much, as I remember it, but by that point in our relationship it was as though we communicated most in our silences.

He photographed me, and I photographed him. And I said to him, “This is a place we’ll always come back to.”

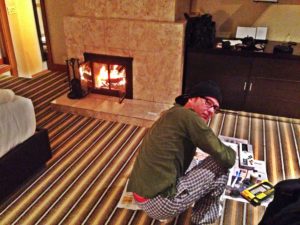

We drove a little further up the coast in the late afternoon and stayed that night in a beautiful cabin that overlooked the Pacific. We watched the sunset together. Then Davyd painted in front of the fire and I read until we turned in. And we slept peacefully.

It was a perfect day. A perfect day in a succession of many perfect days with Davyd, but a day that stands out. Not for any particular reason, but maybe because it seemed we were both entirely present. Because we were alone, undistracted, outside of our normal routine, enjoying each other’s company so completely.

A couple of days after we returned from that road trip, Davyd wrote in his journal, “I’ve felt everything that I’m ever going to feel.” It’s an ambiguous statement, but he was happy on the day that he wrote it (as he evidenced by this picture) and I like to think that what he meant was that he felt the full extent of love, both given and received. I’ve often felt that deep love is not measured in quantity—it’s just a place you get to. And we had arrived at that place; we had reached the summit. I could not have felt any more for him, and he returned love to me in like kind. It was a great, great love, unlike anything I’ve ever known; as close as I’ve ever come to a numinous experience.

One of his paintings that I’ve decided to keep in my personal collection is called BIG SUR. It is the painting that he began in the cabin that night after our perfect day together.

Shortly after Davyd died, I initially thought that I would take his ashes to Virgin Gorda, another place we loved, which we visited a couple of times over the years. But the more I looked at his painting BIG SUR, it seemed to be speaking to me. At first I didn’t know what to make of it—what about this painting suggested Big Sur to him, other than the fact that he started it there?

Then I came across a microscopic picture of sand, full of color and light, and it reminded me of the painting. I have a sense that this might be what Davyd was painting: a microscopic view of the sand with the water rushing through it. As he approached the end of his life, he seemed more and more interested in the macroscopic and the microscopic. He seemed so deeply attuned to nature, and to the idea that we’re essentially one with the universe.

The more I looked at the painting in the months after his death, the more it seemed to suggest to me that Big Sur was where I should spread his remains, in memory of that perfect day, when all seemed so complete.

So I drove up the coast this last Sunday with three of Davyd’s closest friends—Alesia Leingang, Karen Huie, and Suzanne Steck. All three women loved him, supported him, understood him, miss him. And all three of them had traveled with Davyd, when I couldn’t, to various art shows around the country, so somehow it seemed appropriate that they join me on this final trip.

We stayed at the same resort where Davyd and I stayed. We shared stories about him, we cried, and I like to think we all felt him with us in various ways.

We drove down to Pfeiffer Beach early on Monday morning June 1 and I spread Davyd’s ashes in the surf. I’d bought a book of Rumi poems the day before at Nepenthe, and I opened the book randomly to a page. This is what I read:

How much longer

do I have to see these colors

and smell and taste this world

so set inside time?

When will I see my intricate

and subtle soul friend again,

who, when I look at him, I see myself,

who, when I look at

myself, I see him.

I see the one I do not see,

I hear words from one

I cannot be with, that taste

on my lips…

There is pain in this longing,

and not so much what we call joy.

We long for friends, but the healing

of that does not come, just the longing.

I wonder what I will say

when I see him again.

Then I meet my friend

and cannot speak.

I speak to you, not making a sound,

sentences unavailable to ears.

No one’s ear but yours

hear what I say, though

I am speaking to a crowd.

In this book of the heart that we guard, you and I,

you have written something that we must read together.

As you say, Only when

we are alone together.

These words here also are about

that which will be understood only

within each other’s presence.

Not until then.

Not until then, my dear, dear Davyd, but someday. Only love, only love, only love.

Leave a Comment