March 19, 2011

On our recent trip to Rome we went to the Trevi Fountain. Unlike the evocative scene in Fellini’s LA DOLCE VITA, the fountain was not deserted and mysterious. It was instead surrounded by hundreds of tourists, as well as kiosks hawking plastic, miniature versions of Bernini’s sculptures. There was something disorienting about it, and I barely remember taking in the experience of the fountain itself. But it was nevertheless its own kind of wonderful: a crowd of people, teeming with life, energy, and happiness.

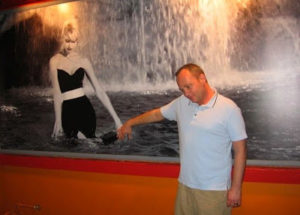

And anyway, there’s always the movie—the dreamlike image of Anita Ekberg walking in the fountain wearing a black dress, with the water cascading over her.

In the film, the protagonist Marcello follows the character of Sylvia into the fountain, desiring her. But they never even kiss—they come close, but they don’t connect, the water stops and they venture out into the dawn without understanding what their experience has been about–the same way we often wake up from a dream that feels unfinished. We’re left wondering what it was which seemed so potent even moments before.

LA DOLCE VITA is broken up into seven episodes which take place over seven nights: each episode ends in the early morning, with an unsuccessful attempt to make sense of the night before. One could say that the film is essentially seven dreams that are to be interpreted by the viewer.

Jaded aristocrats return to a villa in the early morning after a night of debauchery in LA DOLCE VITA. What seemed exciting to the characters a few hours before suddenly feels wearisome.

Fellini’s films often evoke the unconscious—dreamlike images that resonate with the power of archetypes. (He himself spent years in Jungian analysis, and his dream journals are remarkable—you can check them out at this link.)

The opening dream from 8 1/2 symbolizes the protagonist’s sense of being stuck in his creative process.

Giulietta Masina in JULIET OF THE SPIRITS experiences visions that help her process her unhappiness.

I have always loved Fellini, who said about his films: “My work can’t be anything other than a testimony of what I am looking for in life. It is a mirror of my searching…. In this respect, I think, there is no cleavage or difference of content or style in all my films. From first to last, I have struggled to free myself—always from the past, from the education laid upon me as a child. That is what I’m seeking, though through different characters and with changing tempo and images.”

His films offer a real sense of this search, and the heart behind it. His images evoke the emotions of longing and introspection and his movies draw no distinction between high and low culture. His characters often are those that we judge, ignore or discard. He examines the pursuit of love, and also the search for meaning. Watching his films provides a sense of catharsis–I feel more human and more attuned to the world around me after one of his movies.

The manner in which Giulietta is framed against the red wall expresses her emotion in a visual way.

If one watches LA DOLCE VITA, 8 ½, and JULIET OF THE SPIRITS in succession, one can see his “searching” very clearly—characters look for an answer, and the answer is finally to accept the variety of life without resisting its difficulty. Instead they move forward, embracing the totality of experience.

Fellini said, “We must cease projecting ourselves into the future as though it were plannable, foreseeable, tangible, controllable—it’s not; or as though it were a dimension existing outside and beyond ourselves. We must learn to deal with matters as they are, not as we hope or fear they may eventuate. We must cope with them as they exist now, today, at this moment. We must awaken to the fact that the future is already HERE, to be lived in the present. In short, wake up and live!”

The final shot in JULIET OF THE SPIRITS is a visual example of Fellini’s idea of creating a “virginal availability, an innocence from childhood”. It is a very hopeful shot and has stayed in my memory since I first saw the film in college.

But his films are also about looking back; the puzzling through of the factors that have led to our present conditioning, our inability to take in the present. Elsewhere he said, “In three or four of my films, what is constantly repeated is the attempt to suggest to man the process of individual liberation—that is, to trace one’s steps to see where certain dents, certain illnesses started, where the psychological cancers were formed. In going back personally, individually, as a most private artist reflecting on my walk of life, I seem to recognize a certain conditioning of a pedagogical nature of an education that made me suffer, which obstructed me, made me stop. My presumptuous nature leads me to think that it would be worthwhile and just to try to do in my films—as an artist does in his books or another artist in the form of expression more congenial to him—to try to identify what this educational conditioning was, in order to attempt to conquer it, to make it harmless so that the error may not be repeated. I want to suggest to modern man a road of inner liberation, to accept and love life the way it is without idealizing it, without creating concepts about it, without projecting oneself into idealized images on a moral or ethical plane. I want to try to give back to man a virginal availability, his innocence as he had in childhood….

Here then—8 ½, JULIET OF THE SPIRITS, and even LA DOLCE VITA tried to propose this backward walk, tried to identify the pathologic conditioning. What are the myths that must be destroyed? Well, the ideals, the ideals in general. I think that “the ideal”, the idealized life, the idealized concepts can be extremely dangerous for our mental health, and it is what I try to express in my films.”

In other words, our major obstacle to living in the present is some “ideal” that has been suggested to us as to where we should be as opposed to where we are. It is an insidious enemy—this thought that where we are presently is not good enough.

Robert Johnson and Jerry M. Ruhl write in their book CONTENTMENT: “Our society teaches us that the only reality is the one we can hold onto. It values outer experiences and material possessions. Accordingly, we look for contentment ‘out there’ and live with a ‘just as soon as’ mentality. ‘Just as soon as I get my work done, I can relax.’ ‘Just as soon as I get married, I will be content’ or conversely, ‘Just as soon as my divorce comes through, I will be content.’ (etc.) …And so our contentment slips through our fingers like quicksilver—another time, a different place, a better circumstance.”

They go on to write: “Madison Avenue understands our hunger for contentment and uses it as the basis for modern advertising. Soup, automobiles, life insurance—any and all things are sold with a promise either of the satisfaction they will bring or the discomfort they will help us avoid. Advertising infiltrates nearly every corner of modern life, from television and radio commercials to newspapers, magazines, bumper stickers, billboards, park benches, T-shirts, the Internet—even our telephones. All these messages are designed to manipulate us into craving some product or service. We are pulled by desires and pushed by fears. Madison Avenue and the mass media are powerful purveyors of discontent.

But it need not be this way. In any moment, we have the choice to embrace what is happening to us right now as an avenue to a deeper self-awareness.

The Trevi Fountain scene from LA DOLCE VITA has frequently been the inspiration for advertising campaigns. Like the character of Marcello, we’re encouraged to want to climb in to the fountain with the model.

The many dreamlike images from Fellini’s films have inspired me in my own work. His movies create no distinction between reality and dreams, between high and low, between the beautiful and the ugly, the pious and profane.

Fellini’s films appeal to me partly because of the way they turn the mundane into poetry. They capture the fine line between joy and despair. He never judges his characters for the decisions they make, nor does he try to suggest that their problems are resolved. Instead his movies portray the inner images that are inspired by their conflicts and the dilemmas of the external world. He looks at reality, even its ugly parts, but then creates beauty in fantasy and imagination. His characters are presented with a choice of how to view their circumstances and a choice of how to continue. As one character says to Guido in 8 1/2: “…You’re free but you must learn to choose. You don’t have much time. And you have to hurry.”

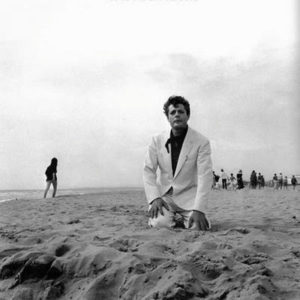

The final sequence of LA DOLCE VITA presents Marcello in a state of ennui, but in 8 1/2 (below) the character Guido celebrates his life by dancing. Ultimately we each decide the response to our fate.

The end of 8½ is appropriately a dance—in the face of life’s contradictions, what else is there to do? Every time I see it I also want to dance.

Leave a Comment