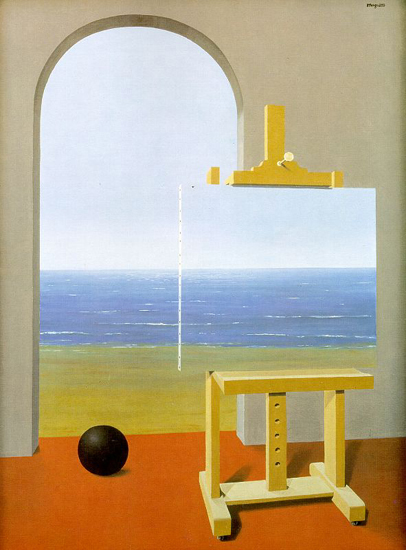

“Everything we see hides another thing. We always want to see what is hidden by what we see.” –Rene Magritte

“Like all revolutions, the surrealist revolution was a reversion, a restitution, an expression of vital and indispensable spiritual needs.” –Eugene Ionesco

November 27, 2011

Walter Murch wrote about film editing: “When you put two shots together, it’s the viewer who makes the connection. The result of this connection may be a completely new idea that wasn’t in either of the two shots to begin with. When you multiply this by dozens, or hundreds, or thousands of edits, you get a fantastic interaction between what’s happening on screen and what’s in the minds of the audience. The mind seems predisposed to do this. My hunch is that it comes from the language of dreams. If you’re lucky enough to wake up in the morning and really remember a dream in some detail, and go over it, you’ll find it has a cinematic quality. For instance, ‘I was in a supermarket, and then suddenly I was in an orange grove picking oranges.’ Those sudden transitions are cuts. If we assume people’s dreams were cinematic before the invention of the motion picture, then what cinema has done is to take the language of dreams and bring it under our control.”

These stills from THE TREE OF LIFE remind me of surrealist paintings.

In fact, it occurs to me that Ionesco’s quote about surrealism also applies to films. Cinema is an attempt to make the spiritual experience concrete—it is “a restitution, an expression of vital and indispensable spiritual needs.”

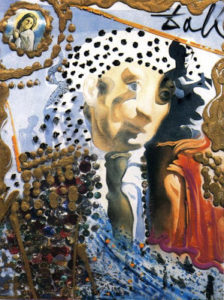

I recently visited the Vancouver Art Gallery, looking at a remarkable exhibit called “The Color of My Dreams: The Surrealist Revolution in Art.” It included, among others, the work of Joan Miró, René Magritte, Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, and Man Ray (Joan Miró’s work has particular resonance as a print of one of his paintings hangs in my bedroom at home—it’s often the last thing I see at night and the first thing I see when I wake up). When we were in Madrid two years ago, a highlight of the trip was the time we spent at the Reina Sofia Museum, where we saw the work of many of these artists. Many of the paintings of the surrealists offer a sense of recognition, something stirring from the collective unconscious. It’s as though I’ve seen these things before, in my own dreams, my own unconscious.Among the works at the Reina Sofia, many of them were collage, similar to editing, in that they’re about making associations.

The Whole Dali in a Face by Salvador Dali

Landscape with a Girl Skipping by Salvador Dali

Surrealism is defined as a 20th-century avant-garde movement in art and literature that sought to release the creative potential of the unconscious mind by the irrational juxtaposition of images. Rene Magritte said, “To be a surrealist means barring from your mind all remembrance of what you have seen, and being always on the lookout for what has never been.” Andre Breton wrote, “Surrealism is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of previously neglected associations, in the omnipotence of dream, in the disinterested play of thought. It tends to ruin once and for all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in solving all the principle problems of life.”

A Chemist Lifting with Extreme Precaution the Cuticle of a Grand Piano by Salvador Dali

I read that statement and it occurs to me that the editing process in cinema can be described, at its best, as a similar experience, or at least there are certain things that can only be discovered by allowing oneself to have “the disinterested play of thought.” For me, great editors are those who encourage the director to get out of the intellect, to discover what it is in the material that wants to come out, separate from conscious intent. There are those directors and editors who dig deeper, that intuit the unexpected, and it is those films that have the most resonance for me, and who separate themselves from the mundane.

Landscape with Butterflies by Salvador Dali

I believe in the “omnipotence of dreams”—it explains why I think cinema and television have such great power on our psyches. The movies that linger in the collective imagination–the films that I’ve written about on this blog, the ones that tend to show up over and over in film books, on websites, in retrospectives, in conversations—capture something of the essence of dreams. The narratives are oftentimes of little or no consequence, except inasmuch as they direct the emotions (that is why exposition scenes are almost always so deadly). But the design elements, the colors or lack thereof, the emotional contexts, the graphic elements—these all stir up the unconscious, and therefore these are the aspects one looks for in repeated viewings.

From THE THIN RED LINE

I started thinking about the films that I’ve responded to, on a visceral level, and about how they often capture the nature of dreams for me. The films of Terrence Malick affect me, not because of their narratives, but because of the way in which they discover “previously neglected associations.” When I first saw THE THIN RED LINE, one of the things that moved me most was the shifting focus, from the brutality of the fighting to the indifference of the natural environment around the soldiers. All of Malick’s films are filled with allusions to the aspect of consciousness that is beyond the duality of good and bad. His movies are often about violence, and then the movement away from violence towards some greater understanding of the world around us. The movements sometimes seem arbitrary and yet they’re not. They’re intuitive, a thought leading to another thought, both illuminated by their juxtaposition.

From THE TREE OF LIFE

Months after seeing it, I’m still thinking about THE TREE OF LIFE, his latest exploration of the nature of being. It’s the kind of film that speaks to the deepest part of me, because it reminds me so much of my own childhood, and my own yearning for a return to the way I felt then—curious, open, hopeful. The much-debated final sequence has much in common with some of the paintings I saw at the Reina Sofia—e.g. the play on perspective and the radical dislocations of a Dali painting, or the mystery of Magritte.

From DAYS OF HEAVEN

And years after seeing Malick’s DAYS OF HEAVEN, I still think of that film too and its doomed love story in a vast, flat landscape. The horizon line itself makes me feel something—the suggestion of other places that one might escape to, both unnerving and hopeful. Malick’s movies are compelling experiences for me because they speak to my feeling, more than to my intellect—the story in DAYS OF HEAVEN is simple and direct. But the images turn me inside out. They remind me of how small a part we play in the flow of nature, and of how little consequence human love affairs actually count.

In her essay about DAYS OF HEAVEN, Adrian Martin writes about the stream of consciousness narration: “In this voice we hear language itself in the process of struggling toward sense, meaning, insight—just as, elsewhere, we see the diverse elements of nature swirling together to perpetually make and unmake what we think of as a landscape, and human figures finding and losing themselves, over and over, as they desperately try to cement their individual identities or ‘characters’.”

There is a sense in these films that nothing endures, that we are simply at the effect of nature’s constant process of destruction and regeneration. There is a repeating motif in most of Malick’s films of old photographs, suggesting people and relationships that no longer exist, and yet there is this concrete image from the past.

Similarly we paint, we write, we make films, in order to create something we might hold onto, making solid our dreams and fantasies. Many of the actors and directors of films I truly loved, from other generations, no longer exist and yet we continue to see what they saw. Their films “hide another thing” and we continue to hope to see beyond the veil.

Recently I found a short student film I made over Christmas in 1978. I was unhappy with the film at the time but, looking back on it, it seems my unconscious was trying to work out something about the nature of dreams. I look at the film now and it makes sense to me in a way that it didn’t then. I was experimenting with the ideas of time and dislocation, and I was trying to see something beyond what was there.

It’s been 33 years since I made this film. There’s something dreamlike about the experience of trying to remember what I felt then.

Leave a Comment