March 14, 2010

This past week I shot a series of fragrance commercials, three for women and one for men. They’re brief and, since the viewer is not able to smell anything, each spot must suggest the “idea” of fragrance through the use of light, design, and texture—and the placement of the actors in the frame. Hopefully, they’ll also succeed in capturing a few moments in time, and will evoke an emotional response in the viewer; make one wish to be next to this man or this woman, and ponder–what comes next?

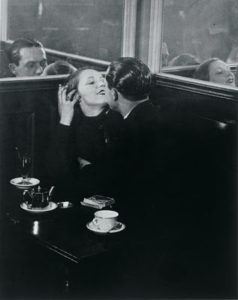

Somewhat like I feel when I look at this photo:

The photo expresses a sense of mystery and romance. What are the man and woman saying to one another? What comes immediately after this moment caught by the camera? Do they really care for each other? Is each genuinely interested in the other, or is each playing out some scene from his or her interior life?

The photo is by the French photographer Brassai, about whom Erika Billeter wrote, “Always astonishing in Brassai’s work is the strong presence of people. They fill every setting with their physical volume and reveal the photographer’s genuine involvement. No photograph was taken just for its own sake. Despite all his transformation of life into a photographic image, Brassai’s pictures were always a confession of humanity….Brassai transposed the everyday elements of human existence into pictures that are full of aesthetic value but also human warmth.” (This particular photo has been my inspiration for this current endeavor–it represents a mood and alludes to more beyond the frame.)

I’m always looking for ideas that inspire me—paintings, photographs, books, architecture, movies, theatre, television shows, music videos, songs, dreams, essays about any and all of the above–anything that makes me feel something, or takes me deeper into my own creative experience. During our trip to Europe this last December, and during our last six weeks in New York, we walked miles through museums, saw films and plays, and spent hours talking about how we were affected by what we’d seen.

In Madrid, we saw LAS MENINAS, a 1656 painting by Diego Velazquez, at the Prado. One could stare at it for hours, contemplating its parts. Wikipedia has a long, wonderful entry about it, well worth reading. Among many other points, it says, “The work’s complex and enigmatic composition raises questions about reality and illusion, and creates an uncertain relationship between the viewer and the figures depicted. Because of these complexities, LAS MENINAS has been one of the most widely analyzed works in western painting.” The experience of looking at it is similar to the experience of watching a film. The painting inspires, because of its precision and density—it suggests imaginary spaces, conversations, and incidents to the viewer, but all of those imaginary events come from within the viewer’s imagination. What is the lady in waiting saying to the young princess? What is the princess thinking? Is the man in the door entering or leaving? I have my own ideas and the person standing next to me will have theirs.

The viewer’s eye is drawn to a mirror on the back wall—and within it there is a reflection of the royals. The king and queen are apparently sitting for a painting by Velazquez (who stands by the easel on the left). They remain a primary point of focus—and yet the painting suggests that the painting is their point of view. Therefore the viewer is allowed to put themselves in the place of the royals—the painting provides an opportunity to feel what they’re feeling as they observe this moment in time. It’s a very cinematic concept, 250 years before the advent of cinema, in that it takes you from an experience of the objective to the subjective by directing your attention to specific elements.

(Also, check this out: 89 SECONDS AT ALCAZAR, a high-definition video by Eve Sussman, inspired by LAS MENINAS. It presents a recreation of the moments leading up to and directly following the moment captured in the painting, when the royal family and their courtiers would have come together in the exact configuration of Velázquez’s painting.)

Picasso seems to have been inspired by this painting as well. Between August and December of 1957, he painted a series of 58 interpretations of LAS MENINAS, which we were also able to see in December at the Picasso Museum in Barcelona. These paintings had a powerful effect on me, in that each represents a different emotional response Picasso had to the original painting. One is able to assess Picasso’s particular focus in each painting by considering which element is allowed to dominate. And the Picasso paintings then create specific responses that allow one to reconsider the original painting.

The green in the Picasso painting on the upper right makes me more aware of the shades of green in the original painting. The focal point of the painting above directs my attention to the courtier entering the room. Or is he leaving?

This is an idea that has always fascinated me—how can one adapt a specific work to emphasize a certain element that is important to the new artist? I frequently study films adapted from books to consider the elements that are illuminated by the filmmaker.

For instance, there is a passage in PRIDE AND PREJUDICE by Jane Austen, describing Elizabeth’s journey through Derbyshire: “Elizabeth’s mind was too full for conversation, but she saw and admired every remarkable spot and point of view. They gradually ascended for half a mile, and then found themselves at the top of a considerable eminence, where the wood ceased…Elizabeth was delighted. She had never seen a place for which nature had done more, or where natural beauty had been so little counteracted by an awkward taste. They were all of them warm in their admiration; and at that moment she felt, that to be mistress of Pemberley might be something!”

This paragraph is interpreted in similar, yet very different ways, in the 1995 BBC version and the 2005 feature version of Austen’s novel. Both filmmakers found the passage important enough to include in their adaptation, and both frame the actress playing Elizabeth (Jennifer Ehle and Kiera Knightley, respectively) against a beautiful view. But the similarities end there. In the former version she turns to her fellow travelers, thus pulling us out of her subjective experience of what she sees. The reverse shot includes the others, and includes them in her thought process as she speaks to them and they to her about the view. The music throughout this scene is unremarkable, continuing a theme that has been playing throughout the entire film without any elaboration, or change in tempo.

This shot from the 1995 BBC version of PRIDE AND PREJUDICE is beautiful, but Elizabeth is turned away from the view. Therefore the viewer is more focused on Elizabeth, objectively, than on the view itself.

In contrast, the 2005 version, directed by the extraordinary Joe Wright, captures the written passage, but then takes it to another level altogether. The wide shot lingers for a very long time, as it tracks to the left, giving us a vast sense of the space, as an analog for deep emotion. At the same time, the score swells, with a dynamic orchestration of a very specific musical theme that has been related to Elizabeth’s inner thoughts. From this wide shot, Wright cuts in close to Elizabeth, from a low angle, with her face against the blue sky, emphasizing a feeling of being on top of the world. No other people are present, no dialogue is necessary to let us know what she is feeling, and the emotional effect is far greater.

I have argued the relative merits of the two versions of PRIDE AND PREJUDICE with many of my friends and students. Many feel that the BBC version is superior for various reasons, but for me Wright’s film sets the bar, not just for this novel but any adaptation of Austen. He has a great visual sense, and it serves the subtext of the storytelling in a more profound way.

Another wonderful example is a sequence adapted from this passage of the novel, after Elizabeth’s friend Charlotte has told her that she is marrying Mr. Collins: “…Charlotte did not stay much longer, and Elizabeth was then left to reflect on what she had heard. It was a long time before she became at all reconciled to the idea of so unsuitable a match.” In the BBC version, the confrontation with Charlotte is staged very conventionally–the two women face each other and are equal in the frame and the subsequent coverage. Elizabeth’s “reflection” takes the form of a quick conversation with her sister in the following scene, where she paces and articulates her disappointment with her friend. Her sister gently chides her, suggesting that maybe there is another way to look at it. The sequence ends with Elizabeth sitting and exhaling with frustration.

In Wright’s version, Charlotte is divided from Elizabeth in the frame by the line of the rope which bisects the frame. The scene is weighted towards Elizabeth, who is presented center frame, in contrast to the over-the-shoulder angle on Charlotte. Charlotte then walks away from Elizabeth, who is left sitting on the swing as she looks after her. Elizabeth spins on the swing as her perspective shifts, and we see the passing of time indicated by the change in light and weather. Rain starts to fall, and in the corner of one POV shot, we see a woman helping a man into the house, out of the rain—a lovely evocation of the helpmeet nature of marriage. Elizabeth continues to spin, a very specific visual representation of someone considering all points of view. Elizabeth’s expression is neutral and meditative, allowing the viewer to project onto the film one’s own emotional reaction. It’s a lovely sequence.

I think Joe Wright’s adaptation of ATONEMENT is equally compelling, and exceedingly skillful in capturing the spirit of the novel.

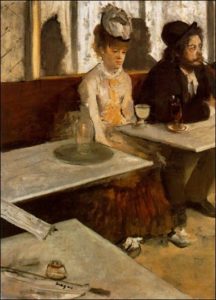

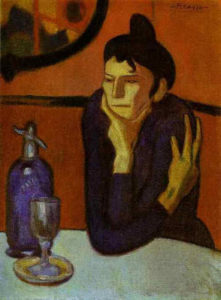

To me, the best adaptations are those that magnify a work—one artist has an idea, and that idea spurs another artist to amplify, to enhance, to bring something original to an existing concept. Take for example, a woman sitting before a glass of absinthe–Degas inspires Picasso, who in turn inspires some advertising executive:

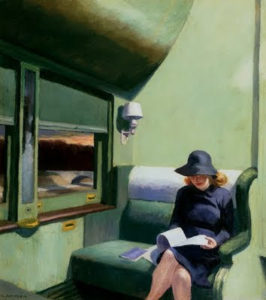

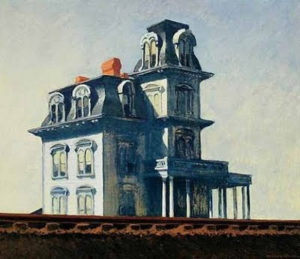

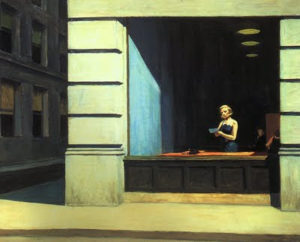

Or consider these wonderful examples of Hitchcock’s inspiration from the work of Edward Hopper (thanks to Joel Gunz for the references):

Expert novel-to-film examples that readily spring to mind for me are THE UNBEARABLE LIGHTNESS OF BEING (a perfect example of how to film a book of ideas, which many said couldn’t be filmed), HOWARD’S END, the two very different but equally compelling versions of THE TALENTED MR. RIPLEY (PURPLE NOON was the first, directed by Rene Clement in 1960), THE AGE OF INNOCENCE (reaching for something that takes one deeper into the novel.)

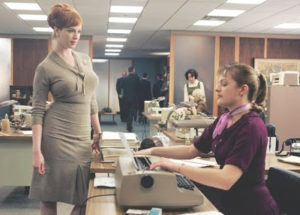

And beyond adaptations, there are the ideas and inspirations that one finds throughout our cultural landscape: on television, MAD MEN includes overt references to films like THE APARTMENT and THE MAN IN THE GREY FLANNEL SUIT.

Closer to home for me, the pilot episode of THE OC echoes themes and relationships similar to REBEL WITHOUT A CAUSE. It is, of course, not a literal retelling, but there is a mirroring of ideas, reinvented to reflect something new for a new generation. The primary relationship between the male and female protagonist in THE OC is set up in a very similar manner—and the experience of the original is then brought to bear upon one’s perception of the new work.

There are, of course, countless other examples. I could go on and on, but the purpose of this post is to encourage your own investigations. To see the similarities–in works of art, in music, in films, and literature—allows one to contemplate the thread of things, to understand that there are ideas that are percolating in the collective unconscious that want to be expressed again and again, for our consideration. Like repeating dreams, the concepts reemerge, to allow one to consider what value and meaning the ideas provide for an evolving consciousness.

Leave a Comment