January 10, 2015

“SYNCHRONICITY was painted at my house, without any memory of painting it. It was painted with enamel house paint and oils on canvas. The title was selected from my obsession with statistics and my belief that all things share a connection, no matter how random. Every person will somehow touch and connect with every other person one day on a social, emotional, or spiritual basis. We are all connected.” –Davyd Whaley

Carl Jung wrote about synchronicity, “It cannot be a question of cause and effect, but of a falling together in time, a kind of simultaneity. Because of this quality of simultaneity, I have picked on the term synchronicity to designate a hypothetical factor equal in rank to causality as a principle of explanation.”

In other words, there’s no explaining what caused it, but it’s real and as important as if you could explain what caused it.

It was Jung’s theory that many experiences which one might see as coincidence actually suggest the manifestation of parallel events or circumstances in terms of meaning, in the realm of archetypes and the collective unconscious. Wikipedia says, “Following discussions with both Albert Einstein and Wolfgang Pauli, Jung believed that there were parallels between synchronicity and aspects of relativity theory and quantum mechanics. Jung was transfixed by the idea that life was not a series of random events but rather an expression of a deeper order, which he and Pauli referred to as Unus Mundus (the idea of one world, an underlying unified reality from which everything emerges and to which everything returns.) This deeper order led to the insights that a person was both embedded in an orderly framework and was the focus of that orderly framework and that the realization of this was more than just an intellectual exercise, but also had elements of a spiritual awakening. From the religious perspective, synchronicity shares similar characteristics of an intervention of grace. Jung also believed that synchronicity served a role similar to that of dreams in a person’s life, with the purpose of shifting a person’s egocentric conscious thinking to greater wholeness.”

Since Davyd Whaley’s death, I have taken much comfort from the synchronicity that surrounds me, reassuring me there’s meaning even in the darkest of times, that there is another way to perceive what is happening.

A couple of weeks ago I took a nap in the early afternoon and I dreamed of Davyd. In the dream he held up his hand to me, in a silent greeting. Later in the evening I went to a play THE CURIOUS INCIDENT OF THE DOG IN THE NIGHTTIME and one of the significant gestures in the play was one character holding up his hand to another, exactly as Davyd had done to me in my dream just hours earlier. I was moved by the synchronicity of the event. And I was quite taken with the play, the story of a young boy, on the autism spectrum, whose senses are frequently assaulted by the world around him.

I have sometimes wondered if Davyd might have been on the high end of the autistic scale, but as far as I know he’d never had any sort of diagnosis in that regard. But I wondered because when I first met him he was a counter. He counted people in a room, tiles along the wall, designs in the carpet; he could calculate vast sums quickly and mysteriously; he could count cards; he understood systems and patterns that would elude me; loud noises bothered him, and his sense of smell was extremely acute. He was very direct and, though he had a wonderful sense of humor, he sometimes would not pick up on sarcasm or irony he was often puzzled by it. He would frequently ask me, “Why don’t people just say what they mean?”

Davyd was always unusual, but there was great, great beauty in his difference, and I found his enormous sensitivity to be one of the most compelling things about him. Everybody else I’ve ever met pales in comparison to his splendid individuality, his complete otherness. For every single day of the ten years we were together I was mesmerized by him and the pain of his absence continues to overwhelm me.

Since his death, I continue to learn more about him through his journals and paintings, but also through his entries on Tumblr, Twitter, and Facebook: things that I glanced over when he originally posted them now take on such extraordinary meaning for me.

Among other things, he wrote:

Painting manifests an alternate universe in which our subconscious world becomes a reality.

What matters is right in front of me. There is nothing else.

Artists never really finish their work. They just find good places to stop and continue their meditations.

He smelled like turpentine, oil paint, and fresh flowers. His favorite color was orange and it went well with his blue eyes.

Be excited about something, love someone, love yourself. Do something.

And sometimes disturbingly, as in the late summer of 2014:

Each day this list of things I care less about increases.

It is very difficult to hold the two opposing thoughts, that Davyd and I were extremely happy together, but also that his life had become untenable for him. I think he was at war within himself, attached to our happiness and life together, but also weary of fighting his internal battles.

Things were going so well for awhile. The years between 2009 and 2013 were great, satisfying years in our lives, and Davyd seemed to have vanquished his demons through his art. I frequently said to people that it was a miracle how Davyd had bounced back from a severe nervous breakdown in 2005 to have such great success.

I have gone back over 2014, which began so promisingly for both of us, and tried to make sense of subsequent events. In retrospect it’s clear that things became more difficult for him throughout the year. In the spring, we discovered a friend had been stealing from us. The betrayal and disappointment was great for both of us, but even worse for Davyd. It triggered his tendency towards suspicion and paranoia. He became obsessed with changing the locks (more than once) and was constantly checking the alarm system in our house.

Additionally, he had been teaching painting to war-scarred children with the Children of War Foundation and to terminally ill children with The Art of Elysium, and while this work gave him great joy and he loved working with children, it also caused great sadness in him about the state of the world. I think his work may have stimulated memories of his own abysmal childhood. One night he was brought to tears about the pain of these children and he said to me, “You don’t understand how difficult it is to suffer when you’re young, and feel that there’s no hope.”

Also, even though he had such great success with his art career, he began to feel he needed more education to make him better able to compete in the art world. He decided he wanted to go back to art school to get his MFA at the Pasadena Art and Design Center. He was immediately accepted at the school, but when he started classes the pressure became too much for him. He had some cognitive problems resulting from his many seizures and migraines, so he decided to drop out after a month. He was devastated he didn’t feel he could continue. He had always done very well in school, so the fact that he couldn’t keep up depressed him. I encouraged him to look on the bright side, that he could get back to his painting, that he always functioned best when he was able to just go to his studio and create. I thought getting back to his daily routine would solve things.

It’s clear now that Davyd was slipping into a fragile mental state in August. I wrote it off to moodiness at the time, and stress. I just thought he was working too hard. But my mother sensed something else was wrong, asking me if Davyd was okay. I insisted he was fine. I was very busy and I was probably in denial about what I did not want to see. He had lost a lot of weight and I did insist that he go to the doctor for a checkup. His doctor told me the weight loss was probably a side effect of his seizure meds — but the doctor also assured me there was no need for concern, and that Davyd just needed to eat more.

I didn’t want to believe that Davyd was struggling with depression and, as a matter of fact, most of the time he hid it from me; from his psychologist and his psychiatrist as well. But I now look back at pictures of him throughout 2014 and see an increasing sadness in his eyes, and a gradual distance. He was moving away from the world, and from his connection to it.

A week before he died, Davyd cleaned and organized his desk, dumped all of his emails, and deleted all but eleven pictures from his Instagram account. In retrospect these details take on great significance, but at the time I didn’t know what to make of it. The eleven pictures he kept on Instagram are comforting to me: pictures of our animals, ourselves, a picture reflecting his volunteer work; all the things that were important to him. And the last picture in the series is one of my favorites: Davyd in front of the LOVE sculpture on 6th Avenue in New York.

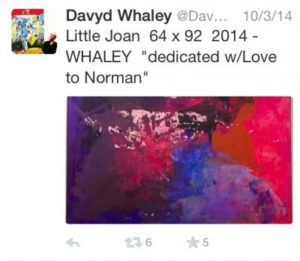

He also framed for me a beautiful painting he’d been working on, that I’d asked if we could keep. He surprised me with it and posted a sweet dedication to me on twitter just a few days before he died.

Things unraveled so quickly at the end that it’s still hard for me to track. In his last week Davyd started to exhibit catastrophic anxiety. He started having nightmares again. He began to panic and had paranoid fantasies; he felt he was being harassed by some unknown stranger. On Saturday night October 11 he woke up in the middle of the night, convinced that someone was trying to break into our house. I tried to reason with him, explaining to him that there was just a party going on next door, and insisted he come back to bed. Sunday morning I sat with him and went over the events of the night before, again trying to reason with him about how he seemed to be connecting random events into some type of pattern where there was none. He agreed that I was probably right, but then in the next breath was asking me, “But who is doing these things? Why are they trying to scare us?”

It occurs to me this is the shadow side of synchronicity: looking for meaning in random events, but in a negative way, reinforcing one’s fears. Davyd began to see the world as a dangerous place and he did not feel safe. I suggested that I go with him in the coming week to see his psychiatrist, to discuss adjusting his medications. He didn’t dispute the idea, but he didn’t agree either.

An hour later he left the house. There was nothing unusual about his departure. I thought he’d simply gone to his studio to paint.and the last thing I said to him was, “Remember that we’re going to the theater at six.” But he never returned and when I drove down to his studio to look for him later that night it was clear he’d hadn’t been there all day. When I tried to call him, the phone went straight to voicemail as though it had been turned off. I started to panic, and I couldn’t sleep at all. In ten years, there had never been a night where we didn’t at least talk on the phone before we went to sleep.

In the middle of the night, the fire alarm started beeping, because of a low battery. I look back on that now as another weird event of synchronicity. Something horrible was wrong but there was nothing I could do.

On Monday afternoon I filed a missing person’s report but the sheriff’s deputy explained they could really do nothing for the first 48 hours. So I called his psychiatrist and his psychologist who both assured me that there was probably nothing to worry about, that Davyd was a problem solver and would probably be home soon. I went through another sleepless night, not knowing where he was.

By Tuesday morning I’d tracked him by credit card to a hotel in Hollywood, but the management at the hotel kept denying he was there and would not help me. I asked them if he’d checked out, but they would give me no information. I called the police to assist me in the middle of Tuesday night/Wednesday morning, when a second charge from the hotel showed up on the credit card. But, by the time the cops got the hotel to cooperate and let them into his room, Davyd had already taken his life. He had not been dead very long.

I have tortured myself wondering what was going through his mind those last two days. There was no suicide note. Instead there were 12 pages of notes, desperately trying to figure out what he should do next, steps to take to solve the problem of his paranoia, and his suspicion of everything around him. He wrote of plans to call his doctors, of coming to see me at work to discuss it with me. All of it was problem solving. Confused and delusional, yes, but there was absolutely nothing suicidal in anything he wrote.

But somehow, at some point during that 60 hour period, something snapped. He gave into some self-destructive impulse and I have been left in a type of existential limbo ever since.

Then a few days after he died I was sitting at my computer when a window opened on my desktop, telling me I’d received an email from a cultural website that I follow with an article about Virginia Woolf’s suicide note.

This seemed such an odd coincidence, so I opened it and read Woolf’s final letter to her husband:

“Dearest,

I feel certain I am going mad again. I feel we can’t go through another of those terrible times. And I shan’t recover this time. I begin to hear voices, and I can’t concentrate. So I am doing what seems the best thing to do. You have given me the greatest possible happiness. You have been in every way all that anyone could be. I don’t think two people could have been happier till this terrible disease came. I can’t fight any longer. I know that I am spoiling your life, that without me you could work. And you will I know. You see I can’t even write this properly. I can’t read. What I want to say is I owe all the happiness of my life to you. You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good. I want to say that everybody knows it. If anybody could have saved me it would have been you. Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness. I can’t go on spoiling your life any longer.

I don’t think two people could have been happier than we have been.”

I sat and looked at the computer for a long time. It occurred to me that if Davyd had written a note to me, then perhaps it might have been similar to Woolf’s; that he indeed sensed the breaking up of his consciousness and couldn’t deal with what that might mean. Davyd had been on heavy psychotropic medications in 2005-2008 and he hated it. He felt they deadened him to life, making him feel lobotomized. I know he did not want to go back on anti-psychotics, and I’m sure he realized it might have been necessary. But I also know for certain that, in spite of the difficulties, no two people could have been happier than Davyd and I have been, and I took comfort from Woolf’s final note.

Initially I didn’t plan to work again until after the first of the year, but by early November I realized I’d go nuts if I didn’t. So I went back to work in early December on a television show in New York. It was hard initially, trying to be focused on something other than my desolation, but it was a good thing to do and I quickly began to feel purpose again. As I was shooting I would sometimes be overcome with sadness, but I would breathe and remind myself that the sadness was the same emotion as the love I always felt for Davyd. And I would begin to feel Davyd around me everywhere. I was staying in a hotel right next to the LOVE sculpture on 6th Avenue, and every time I walked by it I felt Davyd’s presence. I ate at the restaurants we loved, and I sensed him there with me, and I read his journals, which felt like messages to me.

Then on the bar set one particular day I turned to see Virginia Woolf staring at me from a postcard on a bulletin board, a random piece of set decoration that seemed as though it had been placed there just for me. It was so odd, like a small hello. Her pose in the picture was so similar to one of the pictures I loved of Davyd, which I took of him in the last month of his life.

His blue eyes look so deep, as though he’s looking at something beyond what I could see.

A friend actually wrote to me, Davyd always saw things the rest of us don’t. And I believe that. I think Davyd was vibrating at a higher frequency than the rest of us, which was one of the reasons he was so sensitive. Certain people just perceive things in an unusual, powerful way, the way the boy does in THE CURIOUS INCIDENT OF THE DOG IN THE NIGHTTIME. Perhaps those we call autistic, and those who are different, actually understand something we don’t. Maybe they see the Unus Mundus.

In the letter I read at Davyd’s memorial there was the line, “He seems like a person of tremendous physical energy allow the energy that drove his body to reach you now.”

And so I do. I look for that energy all around me. I look for that energy in his journals, in his paintings, in my dreams. I look for it in random messages, in quotes, in poems, and songs, and plays; I look for it in our pets, and I look up in the sky and see the ravens flying by me, and I think, He’s right here, touching and connecting me with every other person, because indeed we are all connected.

Here is a link to an audio of Davyd discussing his painting SYNCHRONICITY:

https://galeriemichaeldavydwhaleyaudio.wordpress.com/2014/02/22/davyd-whaley-synchronicity/

And here is a video describing Jung’s ideas of synchronicity:

Leave a Comment